WASHINGTON — Just three years ago, the future of the U.S. Space Development Agency was uncertain.

Two of its strongest advocates in the Pentagon had resigned, many viewed its mission as duplicative and confusing, and some speculated the organization, created to change the way the military buys and fields satellites, would not survive past its first year. Founded as part of a series of space acquisition and management reforms that included the creation of the Space Force, SDA struggled to make a case for its existence.

Speaking in April 2019 at the annual Space Symposium in Colorado, less than a month after SDA was established, then-Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson offered a scathing take on the agency’s plan to develop a large constellation of small satellites to perform missions like missile tracking and communications, which were traditionally conducted by smaller fleets of large, exquisite and more expensive satellites.

“Launching hundreds of cheap satellites into theater as a substitute for the complex architectures where we provide key capabilities to the warfighter will result in failure on America’s worst day if relied upon alone,†Wilson told the audience.

Wilson, who retired from her post in May 2019 after fighting the creation of SDA and the establishment of the Space Force, wasn’t the organization’s only critic; the House Armed Services Committee said the agency lacked a clearly defined role to distinguish it from other space acquisition offices. Outside experts claimed SDA’s existence created confusion at a time when the Defense Department needed cohesion.

Fred Kennedy, SDA’s first director, told C4ISRNET that any of these factors — congressional confusion, pushback from senior officials and leadership turnover — could have killed the agency before it had a chance to prove itself.

“It could have died any number of ways,†Kennedy said in an interview. “It’s very easy for the dominant culture to walk in and squash those things.â€

But SDA not only survived despite criticism from naysayers; now its model for military space acquisition is catching on.

As the Space Force looks to make its satellites more resilient against threats, it is considering how to integrate smaller spacecraft that can operate in different orbits, leverage commercial capabilities and augment existing systems. Officials, including Vice Chief of Space Operations Gen. David Thompson, have said the need for more resiliency will likely drive near-term budget increases for the service, whose request grew from $17.4 billion in fiscal 2022 to $24.5 billion in fiscal 2023.

Service leaders have praised SDA’s approach, particularly its spiral development process, which emphasizes rapid delivery, regular technology upgrades and fresh competition on a two-year cycle. Speaking in September at the Air, Space and Cyber Conference in Maryland, the Air Force’s top space acquisition official said he wants the Space Force to adopt SDA’s go-fast approach.

“They are building small, they are doing this on two-year centers and they are delivering capabilities faster,†Frank Calvelli said. “I actually think that’s a model that we can take advantage of and actually push across the organization.â€

Congress is also onboard, adding $550 million to SDA’s FY22 appropriations to allow the agency to begin launching its second batch of missile-tracking satellites a year early, in 2025. Lawmakers have broadly supported the agency’s $2.6 billion development and procurement request for FY23.

Even with that turnaround in stakeholder support, SDA still has much to prove. While it’s flown a handful of experimental satellites, it has yet to launch its first batch, or tranche, of missile-tracking and data-relay satellites. That milestone is slated for later this month and will be followed by a second launch in March.

The intent is to showcase those spacecraft in various military exercises in 2023 and to use them to support hypersonic testing in early 2024. SDA will launch its next tranche of more capable satellites in 2024, and it expects its satellites, dubbed the National Defense Space Architecture, will be operational and able to provide global coverage by 2026.

Rep. Jim Cooper, D-Tenn., a leading advocate for space acquisition reform and one of the main proponents for creating the Space Force, told C4ISRNET he’s encouraged by SDA’s plan to disrupt the Pentagon’s status quo. While he’s hoping SDA is successful, he’s also withholding judgment on progress until the agency produces results.

“I was and am optimistic,†Cooper said. “I want to see proof, though.â€

‘Always faster’

The creation of SDA in March 2019 was the first of several major milestones for the military space community that year. In August, the government reestablished U.S. Space Command; it was previously disbanded in 2002. Then in December, Congress authorized the creation of the Space Force, which would operate as a separate service but remain inside the Department of the Air Force.

These moves were aimed at integrating space under one chain of command, but they also were meant to drive improvements to the Defense Department’s space acquisition system.

The commercial space industry was growing, and the military’s process for developing and buying satellites wasn’t taking advantage of that. Plus, lawmakers wanted to ensure these new organizations were designed to go fast.

“A lot of the core concerns that Congress was expressing were about speed of capability development — looking at the commercial space, new space ecosystem, and looking at DoD national security space and seeing things not changing,†Justin Johnson, a special assistant to the deputy secretary of defense from 2017 to 2019, told C4ISRNET.

SDA was created to help the department both emulate the commercial approach and leverage the large constellations companies planned to launch. Modeled after the Missile Defense Agency, which was established in 2002 to test and field ballistic missile capabilities, SDA’s acquisition strategy is defined by two key concepts: spiral development and proliferation.

That means while it traditionally took five to 10 years to conceive and then launch a satellite, SDA wants to shrink that timeline to two years, fielding new technology at a regular pace, or spiral.

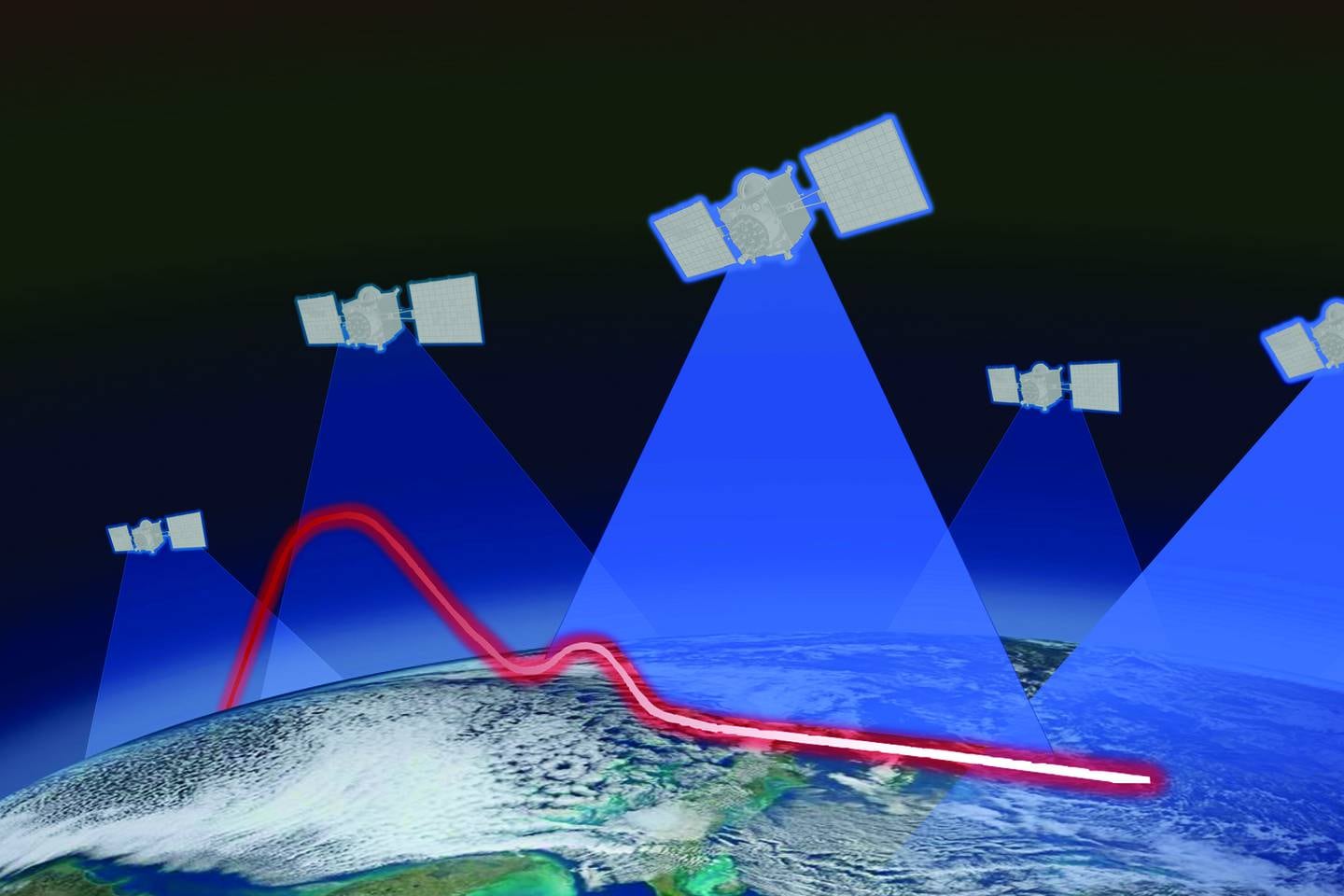

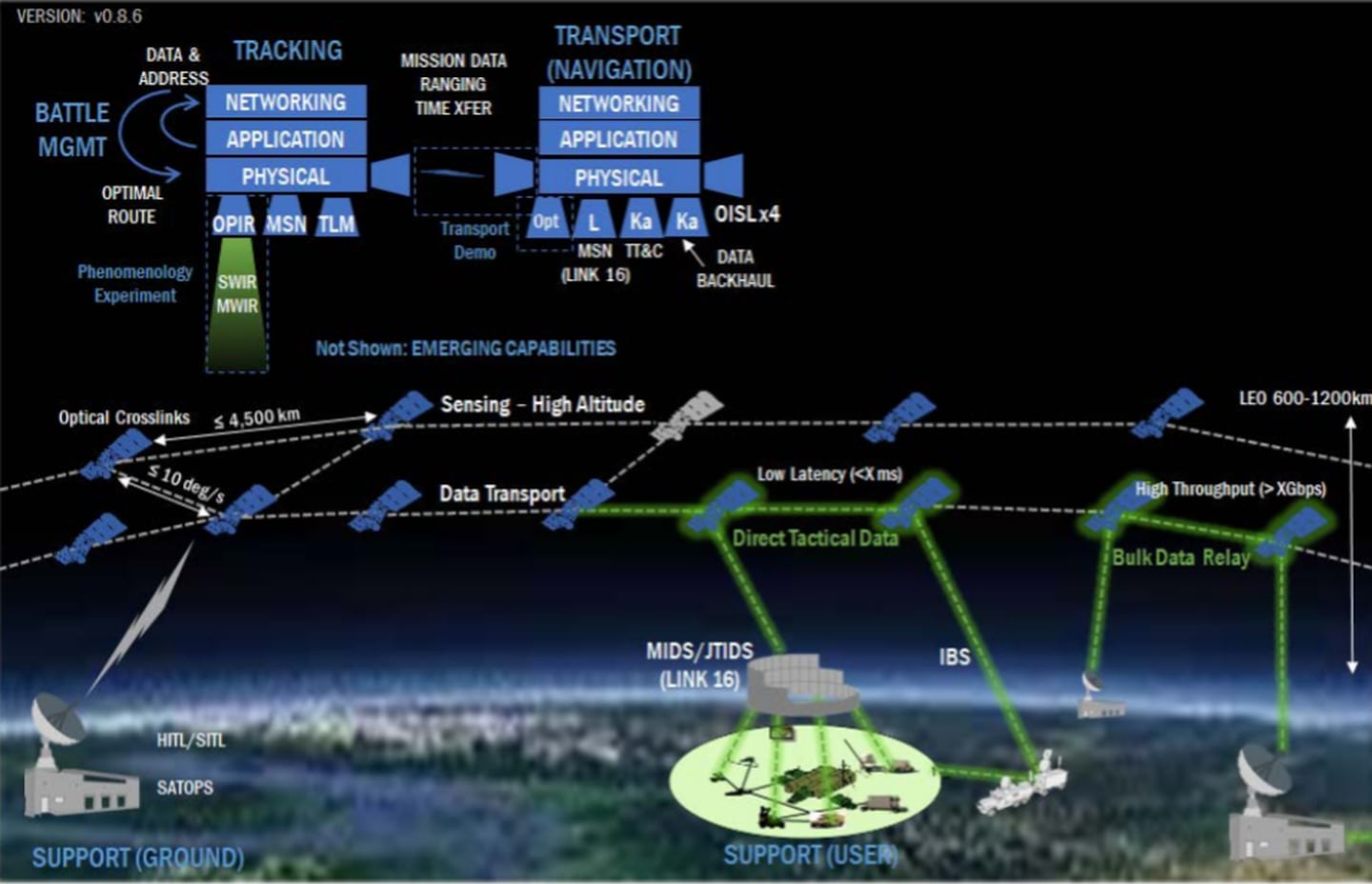

And while military constellations are typically populated with a handful of satellites, SDA’s plan is to have a proliferated fleet of about 1,000 spacecraft on orbit by 2026. Those satellites will reside in low Earth orbit, less than 2,000 kilometers (1,200 miles) above the planet’s surface, and include two capability layers: a transport layer to provide data relay and targeting, and a tracking layer focused on missile warning.

Kennedy, SDA’s first director, adopted the motto “Semper citius,†a Latin phrase that means “Always faster†— a mantra the agency maintains today.

“The thought process behind selecting that motto was the idea that we would do agile development of hardware and software combined, and every time we did it, we would get better and better at it,†Kennedy told C4ISRNET. “It would go faster and [be] less expensive each time we tried.â€

Though the Air Force at the time had its own acquisition hub, called the Space and Missile Systems Center, SDA was designed to be separate from that organization, reporting directly to the undersecretary of defense for research and engineering. The agency transitioned into the Space Force this fall, but the idea early on was that it should have authority over its acquisition processes and have the time to establish itself before becoming part of the new service.

Waning resistance

From the beginning, SDA was backed by then-Deputy Defense Secretary Pat Shanahan, who shepherded the concept in its early days and became the acting defense secretary a few months before the U.S. established the agency. Even with that top-level support, the prospect of creating a new acquisition organization that could duplicate existing work — as well as reside outside of the Air Force and the Space Force — was controversial among some.

Wilson and others in the Air Force argued SDA would add bureaucracy to an already beleaguered acquisition system.

“There was no good reason to establish another departmental-level entity to do procurement of particular space systems,†Wilson, now the president of the University of Texas at El Paso, told C4ISRNET. “This was squarely in the responsibility of the Air Force to equip the force and needed to be directly connected to the rest of the overhead architecture and ground-based control systems.â€

Shanahan understood the pushback from the Air Force, he told C4ISRNET, given new organizations can disrupt the old order and create competition for resources. But he saw a need for an agency like SDA, and there was a growing sense of urgency within the Pentagon and Congress to field more resilient systems capable of withstanding and detecting threats posed by China and Russia.

“There was a lot of friction, and rightly so,†he said. “At the end of the day, it was a leadership decision. ... And I knew once the decision was made, people would support it. There’s always some lingering resistance, but the energy was focused on the threat.â€

Concerns about SDA continued after Shanahan formally established it as an independent agency. But, Shanahan said, he was confident that once the organization had some momentum, its status would be hard to undo. So far, he’s been right.

During SDA’s first two years, it withstood the resignations of Kennedy, Shanahan and then-Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering Mike Griffin — three of its staunchest advocates in the Pentagon. It transitioned to new leadership under Derek Tournear, a former program manager in the Office of the Director of National Intelligence who spent much of his early tenure at SDA explaining the agency’s mission.

SDA awarded its first contracts in August 2020, less than 18 months after its establishment. Lockheed Martin received $188 million and York Space Systems $94 million to each build 10 data relay satellites for its transport layer. Its industry partners now include SpaceX, L3Harris Technologies, Northrop Grumman, Ball Aerospace and General Dynamics.

The agency’s funding has also grown. In FY20, Congress appropriated $125 million for SDA’s initial work; that increased in FY22 to about $1.4 billion. Its FY23 request calls for $2.6 billion, and its five-year forecast projects a need for more than $15 billion through FY27.

Some experts and former DoD officials explain the shift toward acceptance of the agency in different ways, pointing to lawmakers who, while skeptical of the initial articulation of SDA’s mission, gave it room to sharpen its vision.

Kennedy said congressional staffers and lawmakers — including Cooper and Rep. Mike Rogers, R-Ala., two key space acquisition hawks on the House Armed Services Committee — grasped SDA’s mission early on.

“Having that support, having that trust placed in the organization early on by folks over on the Hill, that was extremely important,†Kennedy said.

Johnson, the former special assistant to the deputy secretary of defense, said lawmakers’ early decision to require SDA to transition into the Space Force was helpful because it forced the two organizations to work together in anticipation of that future alignment.

“If you’re a Space Force leader, you knew that at some point ... SDA would be coming back in. So it lessened the incentive to either try to fight or criticize or worry about resources or things like that,†said Johnson, who is now a senior vice president and deputy head of strategy for defense aerospace company Metrea.

“And the same for SDA: Yes, you’re introduced into this ecosystem to create competition, but make sure that you’re staying aligned with the Space Force leadership,†he added.

The reality of threats in space from adversaries such as China and Russia as well as the continued growth of the commercial space industry also helped rally support behind SDA’s mission.

Kennedy, who is now CEO of startup company Dark Fission Space Systems, pointed to the launch of SpaceX’s Starlink communication satellites — which have provided significant support to Ukraine in its fight against Russia — as well as Amazon’s plan to launch its own satellite communications network, called Project Kuiper. Those commercial projects bolster SDA’s premise that such a development model can be successful and offer opportunities for the government to leverage industry growth, he said.

“Reality gets to intrude from time to time. And in this case, you’ve got Starlink, you’ve got Kuiper, you’ve got all sorts of folks who are driving down a very similar path. And it should come as a shock to nobody,†Kennedy said. “SDA was stood up to essentially pattern itself after commoditized, productized, proliferated systems. It’s happening in the commercial sector. Why can’t we do it, too?â€

Will SDA prove itself?

Much of the early pushback against SDA is “water under the bridge,†according to Doug Loverro, former deputy assistant secretary of defense for space policy. Now, the agency must maintain that support by proving it can field its proliferated architecture on schedule.

“Success breeds support,†Loverro told C4ISRNET in an interview.

Starting this month and over the next year, SDA will have several opportunities to build confidence in its performance. The first launch in support of its National Defense Space Architecture — which will include demonstration satellites for what it calls the Tranche 0 transport and tracking layers — is scheduled for sometime in December, followed by a second Tranche 0 launch in March.

Those first 28 spacecraft are meant to support several military exercises in 2023 and 2024, including U.S. Indo-Pacific Command’s Northern Edge, a joint readiness event that takes place every other year and is planned for next summer.

Speaking during a National Security Space Association event in November, Tournear said he’s confident in SDA’s near-term plans, though he acknowledged it’s not a “zero risk†approach. In fact, the December launch, which was already delayed from September due to early contractor protests and pandemic-related supply chain slowdowns, could slip again, he said.

“There’s obviously risk there because we are pushing industry to go as quickly as possible,†Tournear said. “There’s not a lot of margin. But Lord willing and the creek don’t rise, we won’t have any issues with the integration, and we’ll hit that launch.â€

Tranche 0 is what SDA calls its “warfighter immersion†capability and will demonstrate the viability of its proliferated architecture — from cost to schedule to scalability. Tranche 1, which is targeted for launch in FY24, brings an initial warfighting capability, will showcase tactical data links and beyond-line-of-sight targeting for the transport layer, and will provide advanced missile detection for the tracking layer. The next group of satellites, Tranche 2, will bring global persistence for both layers and is slated for launch in FY26.

Loverro said the technical challenges associated with SDA’s mission will get harder as it moves toward Tranche 2 and its architecture becomes more fully integrated with the joint force. Earlier capability releases will be more like demonstrations or prototypes, but Tranche 2 will need to operate in a warfighting environment.

While the agency has garnered praise from Space Force and Air Force leadership, its work over the next year could also have implications for its longevity as an independent acquisition organization. Johnson said he’ll be watching the FY24 budget as an indicator for how the Department of the Air Force prioritizes the agency’s efforts.

“Do they get squeezed by other priorities, or does the fact that they’ve had time to establish themselves independently inside [the Office of the Secretary of Defense] give them enough stability inside of what’s now the Department of the Air Force ecosystem?†he said. “I think the next budget request will be an interesting indicator of how SDA is doing in maintaining its vision and independence.â€

Courtney Albon is C4ISRNET’s space and emerging technology reporter. She has covered the U.S. military since 2012, with a focus on the Air Force and Space Force. She has reported on some of the Defense Department’s most significant acquisition, budget and policy challenges.