WASHINGTON — In March 2019, the Pentagon established a new organization to buy space systems: The Space Development Agency. But this led to some confusion.

After all, the U.S. Air Force’s Space and Missile Systems Center already bought the bulk of the military’s satellites and space systems, and the Space Rapid Capabilities Office acted as a supplement to drive faster programs.

The imminent establishment of the U.S. Space Force brought further questions: Why set up a new space acquisitions organization when the military was on the verge of reorganizing its main space acquisitions service? Some suggested that the nascent agency wouldn’t survive the year.

RELATED

Over the intervening 18 months, the Space Development Agency, or SDA, has embarked on a whirlwind tour to not only explain what it’s building, but how it offers something different than legacy organizations.

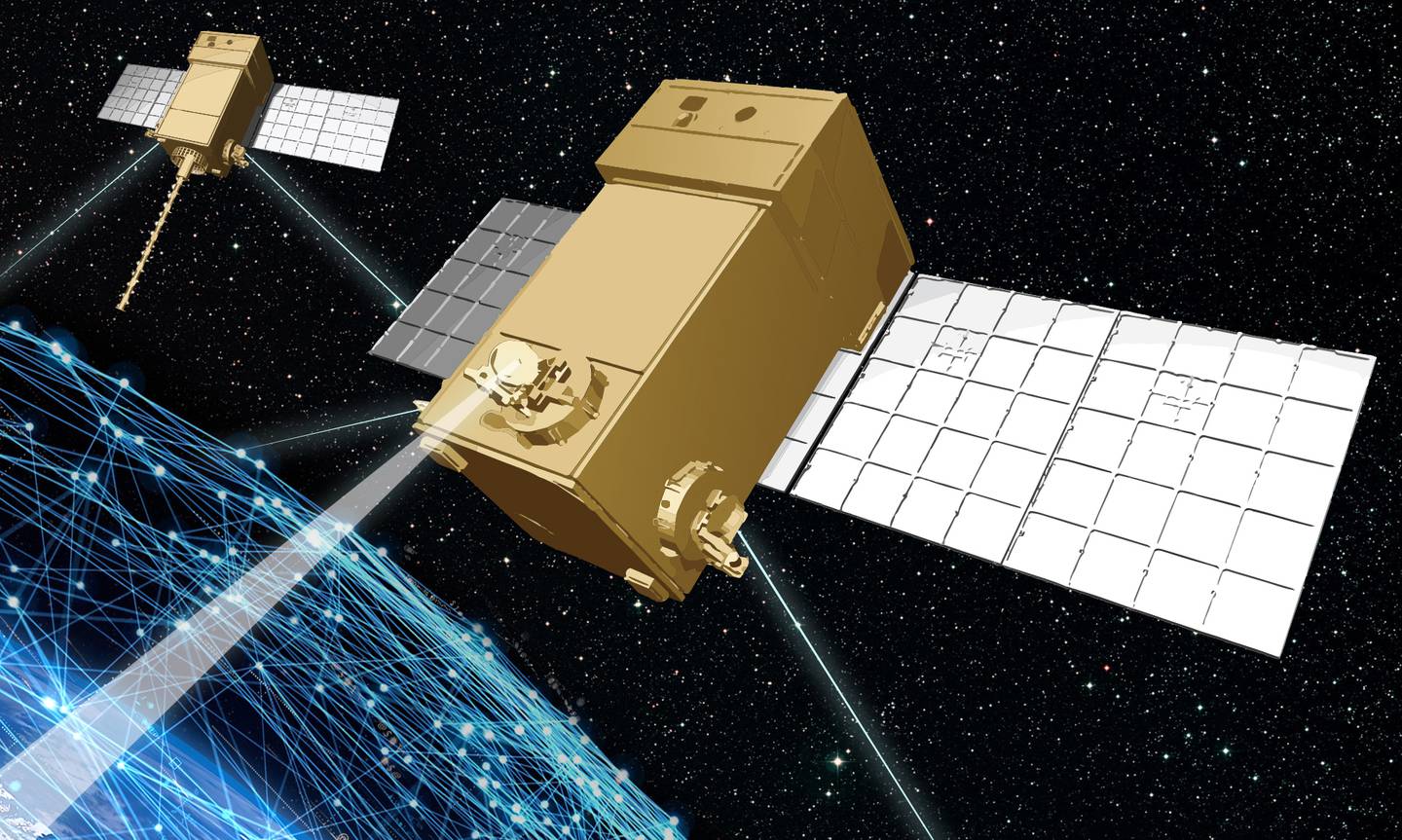

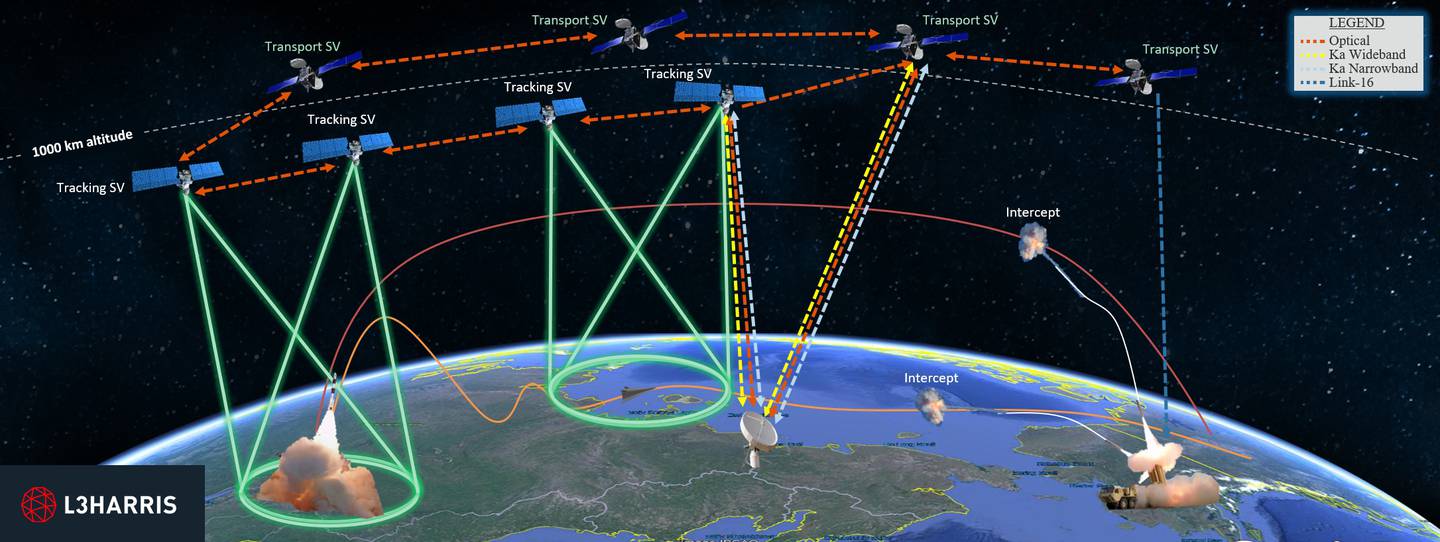

To the first point: SDA was set up to build the National Defense Space Architecture, a new proliferated constellation primarily in low Earth orbit that will be made up of hundreds of satellites. That’s a radical departure from traditional military space. To date, the biggest military constellation in operation is GPS, with about 30 satellites ― give or take a satellite or two ― on orbit at any one time. With the new architecture, SDA wants to put into orbit about 1,000 satellites by 2026.

“It’s got this novel approach compared to, you know, kind of the legacy approach. They’ve got these very unique core values. So they do things quickly. They’re a very lean organization. They move out fast. They’re responsive to the needs of the war fighter,” said Mark Lewis, the Pentagon’s acting deputy undersecretary of defense for research and engineering.

Over the last 18 months, the agency has designed the National Defense Space Architecture, or NDSA; issued its first request for proposals; and awarded its first contracts. Here’s what onlookers have seen in how the agency works differently:

Gotta go fast

The area where SDA has most distinguished itself is speed, according to some observers.

“A lot of the reason the SDA was stood up is that there is a general recognition that the speed of the threat is increasing tremendously,” said Eric Brown, director of mission strategy for military space at Lockheed Martin, one of the companies providing satellites for the NDSA. “Everyone is acknowledging that in order to stay ahead and maintain our high ground from a space superiority standpoint, we’re going to have to operate at a different speed.”

At an industry day in summer 2019, SDA Director Derek Tournear laid out the agency’s plan. In 2022, just three years after SDA was established, it would launch its first satellites ― a little more than 20. Most military constellations consist of less than a dozen satellites, and it can take five to 10 years from conception until the first satellite arrives at the launch pad.

SDA’s plans didn’t stop there. The agency planned to launch increasingly large numbers of satellites into orbit in two-year tranches, culminating in a constellation of about 1,000 satellites in 2026. With this spiral development approach, the agency is looking to put mature technology on orbit now, and then provide upgraded capabilities as more tranches go online.

In other words: In less time than it traditionally took the Air Force to design and launch one satellite, SDA wanted to launch 1,000.

In the resulting 18 months, the agency has set a goal of launching its first satellites two years from now.

“I certainly have to applaud SDA. In every case over the past year and a half, when they have set a date they have met that date,” Brown said. “They really kept to a very tight schedule, which is certainly impressive, especially for an agency that’s only just standing up.”

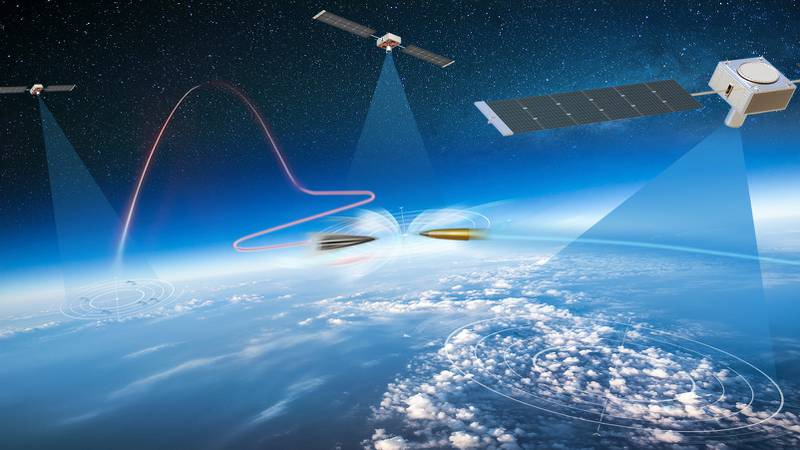

SDA issued its first request for proposals on May 1, seeking 20 satellites for its transport layer. Later that month, it issued another solicitation for eight wide-field-of-view satellites for its missile-tracking layer.

“They’ve done things that we’ve never seen before,” said Bill Gattle, the chief executive of L3Harris Technologies' space systems business. “They were able to release a request for proposal very quickly, and it was actually a pretty good request for proposal.”

Gattle said SDA was unusually clear in laying out what it wanted and that the agency had one priority: speed. SDA wanted vendors who could stick to their aggressive schedule and deliver satellites in two years' time.

“They only gave industry 30 days to respond (for each request for proposal),” Gattle said. “That is unprecedented speed ― we normally get 45, 60 days.”

Moreover, while it typically takes months to get feedback from the customer, SDA responded within three weeks, offered the proposers notes, and required updated submissions back within two weeks, recalled Gattle. “And then they awarded about two to three weeks later. That compressed timeline was stunning.”

In August, the agency awarded Lockheed Martin and York Space Systems $188 million and $94 million respectively to each build 10 of those satellites. In October, the agency announced two more contracts: SpaceX and L3Harris would receive $149 million and $193 million respectively to each build four wide-field-of-view satellites for the NDSA’s missile-tracking layer. Neither York Space Systems nor SpaceX responded to requests from C4ISRNET to discuss the contracts.

RELATED

“It demonstrates SDA [is] doing what it was created to do, which is to quickly obligate funds, move really quickly and execute toward the mission,” Lewis said, referring to the contracts.

“It shows one of the values of SDA as kind of an independent organization in delivering this tranche 0,” he added. “It’s not clear that a larger, more bureaucratic organization culture could have moved as quickly as SDA did.”

Bringing in the new kids

Program officials sometimes talk a big game about bringing in nontraditional vendors, yet end up awarding to the same small group of contractor giants over and over again. But with its first batch of four contracts, the agency has already brought in some surprising names.

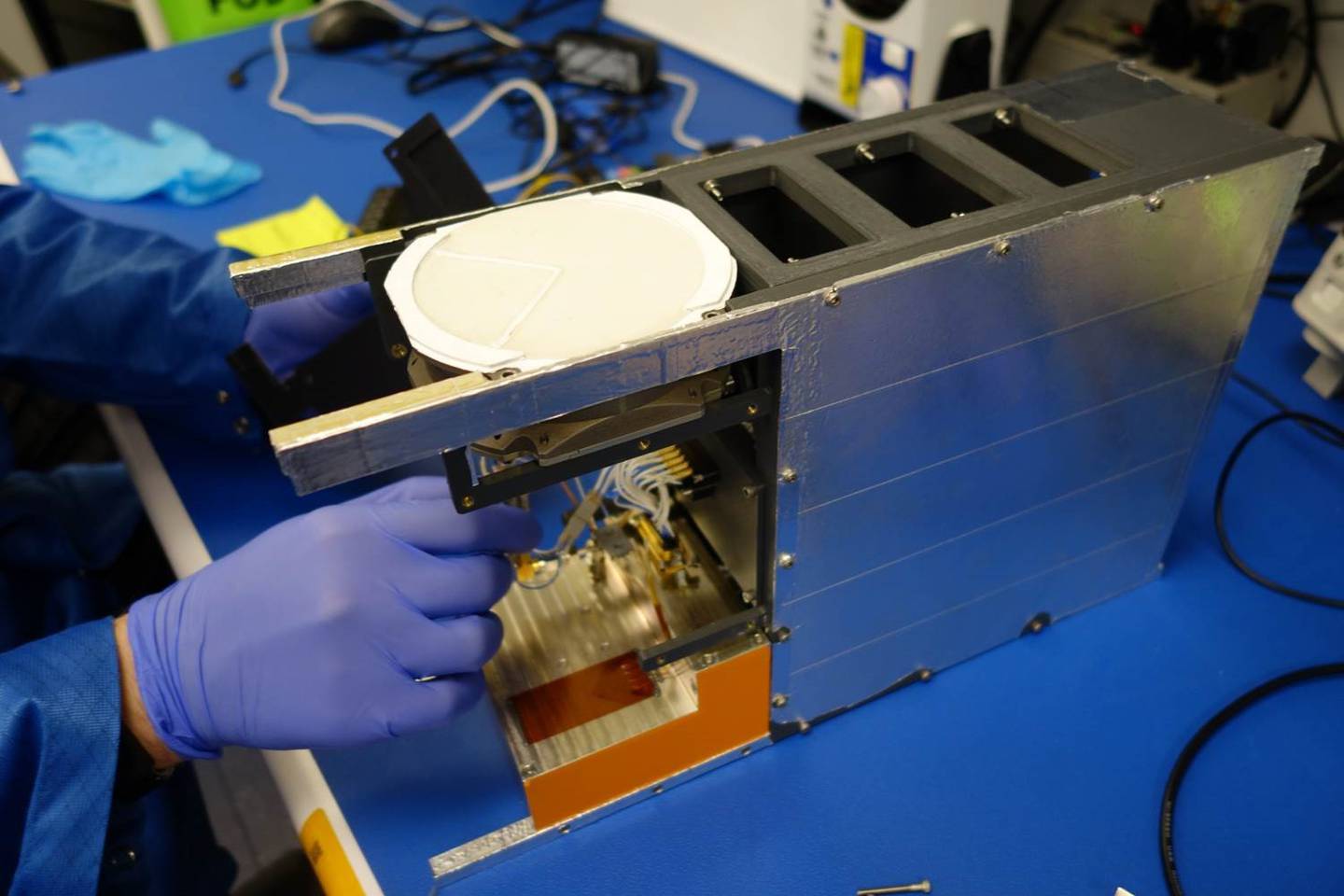

York Space Systems, which will be building 10 transport layer satellites, has never built a major satellite for the Air Force or Space Force. The small satellite manufacturer has done some experimental work with the military, but this seems to be the company’s first major contract win with the Pentagon.

SpaceX may be the most recognized company in the world when it comes to space, but to date the firm’s efforts have been limited to launch services and satellite-enabled commercial broadband. SpaceX has scrappily fought over the last decade to win more national security launches, and earlier this year it was named one of two companies providing heavy launches for the Space Force over a five-year period. Additionally, the company’s Starlink constellation has helped popularize the proliferated constellation concept on which SDA is built, and the services have begun experimenting with Starlink to enable beyond-line-of-sight communications.

Still, this will be the first time SpaceX has built a satellite for the military.

Neither York Space Systems nor SpaceX responded to requests for comment.

L3Harris Technologies may not be a newcomer when it comes to supplying technology to the military, but many were likely surprised to see the company selected to build the missile-tracking satellites that will be key to the Pentagon’s efforts to defeat hypersonic weapons. L3Harris has not built a missile warning satellite for the U.S. military before; its forays into infrared sensors was limited to weather satellites until now.

“We were known pretty much as a weather company in this area, infrared,” Gattle admitted. “This is the culmination for us of a pretty big pivot in our company.”

A couple of years ago, L3Harris decided to apply its weather-sensing infrared technology to missile tracking, with a focus on the types of satellites the military was signaling it wanted: affordable and quick to produce. In October, that bet seems to have initially paid off with SDA.

“The industry people, including us, are all repositioning our companies to address basically the message that space has to be a war-fighting domain, space has to be more affordable, space has to have easier access, where you can get there faster,” Gattle said. “I think for a lot of us in the industry, we view this as probably the biggest transformation we’ve seen since the Apollo days.”

Of course, Lockheed Martin stands out in the group as a defense giant — one of the companies that’s always in the discussion when selecting a military satellite manufacturer — and naysayers may point to the firm’s inclusion as proof that SDA isn’t reinventing the wheel. The company itself is quick to acknowledge its role in the status quo, but Brown credited the contract win to Lockheed’s ability to be disruptive and quickly refocus its energy.

“We’ve demonstrated — and have been told from SDA — we’ve demonstrated that we’ve built upon Lockheed Martin’s history of being disruptive,” Brown said. “We’ve had some success in the past and people have stopped associating us in some way with disruption, but this was a place where we really wanted to demonstrate something very differently from what you would see in some of our existing programs of record.”

A key example of the company’s pivot from exquisite space systems to proliferated constellations is Pony Express, Lockheed’s experimental on-orbit mesh network. Developed in nine months, Pony Express was privately funded by the company to test new space-based computing capabilities that could enable on-orbit artificial intelligence, data analytics, cloud networking and advanced satellite communications. In other words, it was testing some of the very capabilities with which SDA wants to enable its own on-orbit mesh network.

“We saw the requirements coming for transport layer — frankly, it’s the capability that the U.S. government has needed for some time,” Brown said. “Pony Express really marked a little bit of a graduation, being able to show the community and show the world the kind of capabilities that Lockheed Martin had been investing in and developing for some time.”

Lockheed brought forward some of the technologies developed for Pony Express to the transport layer. In addition, Brown claimed, the company’s proposal included plans for a diversity of subcontracts in building its satellites, helping to expand the industrial base for SDA’s future tranches, which will include a massive increase in the sheer number of satellites purchased.

“We made a conscious choice not to take a heavily vertical approach because we don’t think that that sort of vertical play that you might see from some other companies would have really benefited the SDA,” Brown said.

Learning from industry

Tournear has his own example of how his agency is unique, and it showcases how SDA wants to act like a commercial entity. Just as the agency awarded the two contracts for its first tracking layer satellites, it also canceled a contract for an experiment meant to reduce risk on those satellites.

“We canceled that experiment because what we do at SDA is we continually look at measuring the return on investment to get the best capability for the taxpayer dollar, and we view that as the investment going forward,” Tournear said.

“The tracking phenomenology experiment was started before tranche 0, with the idea that it would do two things. One, it would burn down risk for tranche 0 WFoV [wide field of view],” he added. “And number two, it would give us OPIR [overhead persistent infrared] bands that were multiple bands.”

As the agency began receiving proposals, it became clear that some of the proposers were already including multiple bands on their OPIR solutions. In other words, SDA didn’t need to develop its own solution for that capability — instead, industry could provide it.

Still, the experiment would offer valuable risk reduction, giving the tracking layer a greater chance of succeeding. SDA decided to calculate whether it was worth continuing the experiment.

RELATED

“We had to look at the cost going forward to carry the tracking phenomenology experiment, subtract from that the risk leans that it would burn down in the WFoV experiment, and calculate, in essence, our net present value going forward,” Tournear explained. “So in that respect, canceling that program saved us a total net present value of $20 million.”

One contributing factor was the knowledge that the experiment was only going to deliver data nine months prior to the satellites being delivered. That was not a lot of time to factor lessons learned into the final product.

Additionally, the agency didn’t have enough money allotted to buy all eight missile-tracking satellites. But by canceling the contract, SDA could apply the $20 million to buying more of them.

“In order to ensure we get the best capability to the war fighter, the return is higher to invest that money toward getting more of the WFoV sensors up on tranche 0,” Tournear said. “That is a calculus that you don’t often hear being made by the government on these programs. But it does show that we are trying to respond in a rapid manner to get these capabilities fielded as quickly as possible, and we’re going to do trades to make sure that we push forward with getting those capabilities fielded."

Tournear declined to say how many satellites the $20 million from the experiment bought, only noting that it enabled the agency to get the eight total satellites it wanted for tranche 0.

“They’re making good decisions. The ability to stop things that aren’t working — I think that’s really important. The ability to start things quickly — that’s also really important,” said Lewis.

Nathan Strout covers space, unmanned and intelligence systems for C4ISRNET.