COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. — About a year ago, the Space Force established a combined program office to ensure that the three Pentagon agencies building the next generation of missile warning and tracking satellites were functioning as a cohesive unit.

So far, according to officials, the arrangement has worked.

Space Force Col. Brian Denaro, Space Systems Command’s program executive officer for space sensing, and Army Col. Alex Rasmussen, program manager for the Space Development Agency’s second tranche of missile tracking satellites, told C4ISRNET that without regular collaboration with their respective teams and their counterparts at the Missile Defense Agency, they would likely have faced unexpected development challenges.

Within the combined program office construct, the agencies meet weekly through an integration working group to share technical information. They also convene quarterly “summits†to troubleshoot any challenges they’re facing and prioritize and assign tasks for the working group.

“There are absolutely things we would be missing,†Denaro said in an interview this month at the Space Symposium in Colorado Springs, Colo. “Those groups have ferreted those things out and helped us get after them.â€

The Pentagon’s space acquisition offices have struggled in the past to agree on their roles and align their work to avoid duplication — particularly within the space-based missile warning mission area. Lawmakers and watchdogs including the Government Accountability Office have criticized the department’s lack of coordination, particularly between the Missile Defense Agency and the Space Development Agency, which are developing sensors to track hypersonic missiles.

Last year, the Space Force’s program integration council — which includes officials from Space Systems Command, the National Reconnaissance Office, MDA and the Air Force Rapid Capabilities Office — approved a strategy for the Defense Department’s future space-based missile warning satellites and ground systems.

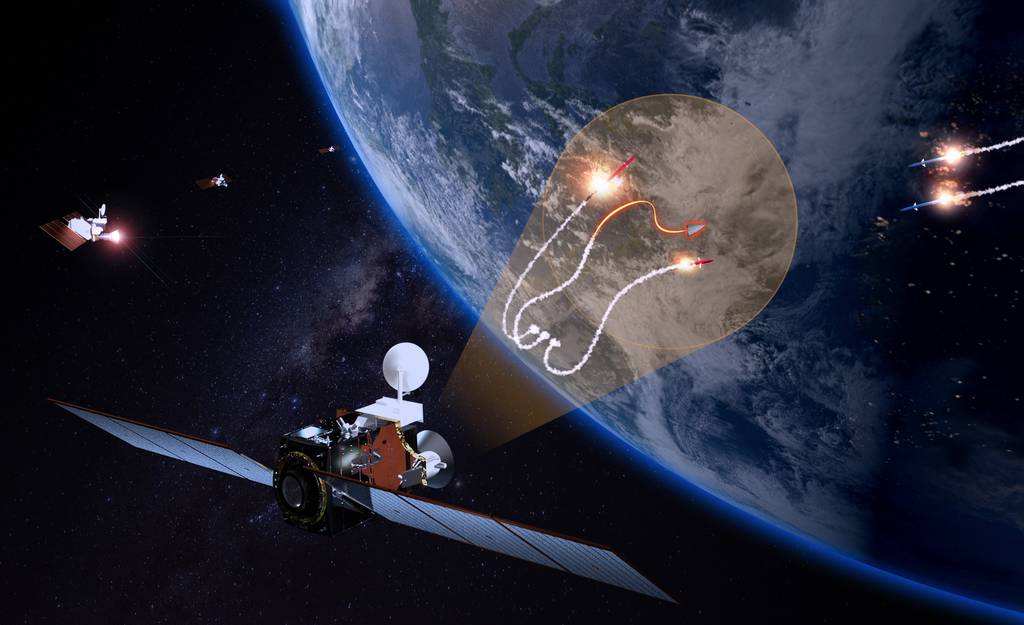

The strategy calls for a new approach to detecting and tracking missile threats from space, a mission the Space Force has traditionally conducted from geosynchronous orbit, roughly 22,000 miles above Earth. As Russia and China develop hypersonic missiles that can maneuver and travel at Mach 5 or faster, the strategy calls for improving U.S. defenses against those weapons by launching smaller satellites to more diverse orbits.

It also endorsed the creation of the combined program office and clarified responsibility for various elements of the architecture.

Under the strategy, the Space Development Agency is responsible for fielding smaller satellites that will reside in low Earth orbit, about 1,200 miles above the planet. Space Systems Command will continue to develop the GEO layer as well as a medium Earth orbit constellation, which will reside between LEO and GEO. The organization is also leading efforts to build a ground control segment that integrates systems from the three agencies.

MDA, meanwhile, is developing medium-field-of-view sensors through its Hypersonic Ballistic Tracking Space Sensor program, or HBTSS. The sensors are designed track dimmer missile targets and send data to interceptors. The agency’s role is to demonstrate the capability, which the Space Force will ultimately take over and incorporate into the broader missile tracking constellation.

Denaro and Rasmussen said the regular working group meetings and summits have not only helped clarify roles among the agencies, but they’ve created a venue for them to learn from one another. For example, Rasmussen said that as MDA plans to launch its HBTSS satellites later this year and begins testing the capabilities in orbit, SDA will collect data from those demonstrations and opt to either integrate the sensors with its future satellites or continue to refine the technology.

“Even if HBTSS doesn’t end up in part of the future tranches, all that tech that they learned, all of that stuff that we were able to do in the demo, it’s absolutely advancing our mission,†Rasmussen said.

MDA officials have also indicated improved collaboration with the Space Force. In a March 14 budget briefing, the agency’s director, Vice Adm. Jon Hill, said the combined program office is helping the teams avoid “redundance and duplication.â€

Denaro said because of the summits, SDA and SSC decided to co-fund technologies that both agencies will need for their pieces of the program. This includes capabilities like focal planes, which satellites use to collect real-time imagery, and crosslinks, which allow systems to communicate.

The collaboration has also helped address common supply chain issues. Over the next five years, the agencies plan to launch more than 100 missile tracking satellites combined, which means they need to be aware of any vulnerabilities within their supply base, Denaro said.

“We’re absolutely looking at the supply chain to make sure that . . . the supply chain is not a weak link in the chain, if you will, and that we’ve anticipated any potential disruptions or concerns on the supply side,†he said.

Rasmussen said the coordination among the agencies also helps industry view their work from an enterprise level and have a better sense of the various opportunities to compete for development contracts.

He said SDA and SSC have deliberately staggered their schedules, which makes competition “consistent and predictable.â€

“That really tells industry, ‘Hey, make the investments. You know we’re going to compete this. You know we’re going to compete every tranche,’†he said.

Courtney Albon is C4ISRNET’s space and emerging technology reporter. She has covered the U.S. military since 2012, with a focus on the Air Force and Space Force. She has reported on some of the Defense Department’s most significant acquisition, budget and policy challenges.