In the four months since it was officially established, the Space Development Agency has been a bit of a mystery.

After Pentagon leaders asked for a new space architecture, it wasn’t clear whether the SDA was meant to replace the Pentagon’s existing satellite systems, incorporate them into its own architecture or take over responsibility for the current constellations. The agency released a notional architecture along with a request for information July 1, but that only seemed to fuel questions about how the agency’s plans would affect the Department of Defense’s existing systems.

RELATED

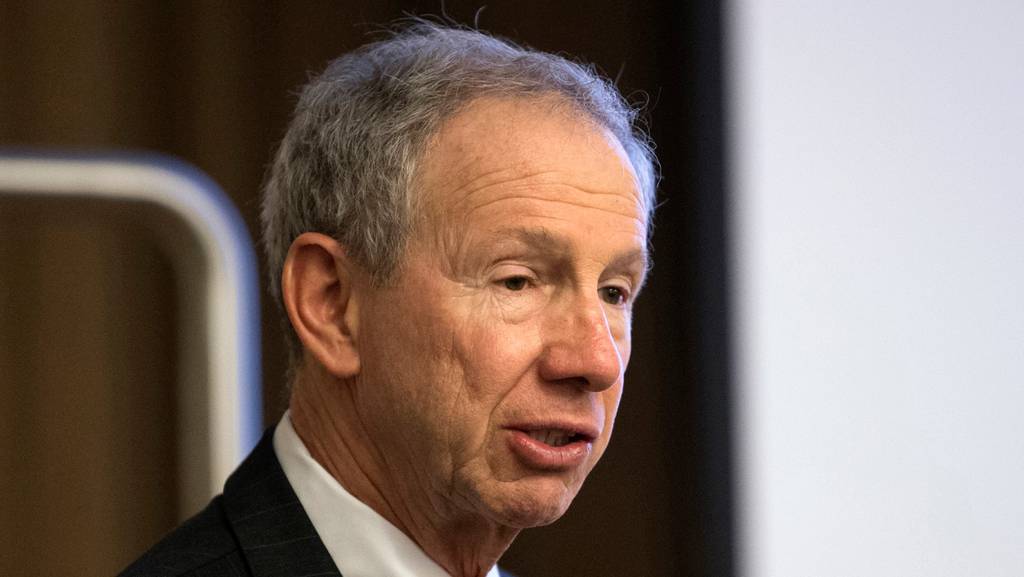

Mike Griffin, the Pentagon’s under secretary of defense for research and engineering, said July 23 the SDA “is not the owner and arbiter of all things space for the national security community,” but what exactly is the agency’s place when it comes to space? At an industry day in Chantilly, Virginia, SDA leaders explained the agency’s mission and what makes it different than existing military space organizations and systems.

Resiliency via numbers

A major concern with the military’s current space architecture is that it is composed of small constellations of large, exquisite satellites. With each system being made up of so few satellites, the successful destruction or disabling of just one satellite can have a significant impact on the battlefield.

Recent war games have highlighted the vulnerability of American military satellites, Griffin said. American and allied forces have been disadvantaged in those games, he said, because adversaries quickly target the military’s few satellites.

“We don’t want to perpetuate a constellation of juicy targets,” said Griffin. “We want to confound the adversary.”

As a result, the SDA is committed to creating an architecture that provides “resiliency via numbers,” said Derek Tournear, the agency’s acting director. Instead of a space architecture characterized by a small number of large, expensive satellites, the SDA’s vision consists of hundreds of small satellites possibly hosting multiple payloads, all operating in a mesh network. Whereas the loss of one or two satellites in the military’s current systems could be crippling, a constellation of hundreds of satellites can brush off the loss of one or two space vehicles.

RELATED

“It also takes a much larger and more concerted attack to take out a given percentage of capability,” explained Griffin. “Proliferation of our systems, where each individual asset has less capability but in aggregate they have all that we need is the path that we want to go down.”

Avoiding unnecessary redundancy

The SDA will not oversee every Air Force satellite system. Key programs such as the Advanced Extremely High Frequency system, the Next-Generation Overhead Persistent Infrared program, the Wideband Global SATCOM system and GPS are outside of the architecture SDA leaders are developing.

“The SDA does not want to build every satellite needed for the future National Defense Space Architecture. There are many partners already developing capabilities, which we can and will incorporate,” said Tournear.

Griffin specifically noted that the need for a proliferated space architecture did not mean that the Air Force should not continue using and building exquisite satellite systems.

“[Space and Missile Systems Center] will continue doing what they’re doing,” said Griffin. “There’s no overlap there.”

The SDA’s focus on resiliency helps explain which satellites the SDA wants to build. In the near term, the agency’s goal will be to augment the Air Force’s existing programs or provide back-up systems for the times those satellites are unavailable.

The most obvious example of this is the architecture’s position, navigation and timing layer. The military generally relies on the GPS constellation of satellites for position, navigation and timing data. The SDA architecture will provide alternative PNT data that the military can rely on when GPS is unavailable. Such a navigation layer would be redundant in that it would provides a service already widely used, but is valuable to the military because it would increases the resiliency of PNT data.

Other layers will serve as complements to other Air Force satellite systems. The proposed tracking layer would assist the OPIR satellite system, not replace it. However, it’s worth noting DARPA documents suggest that OPIR payloads could be hosted on their experimental Blackjack satellites.

“SDA is responsible for developing and fielding capabilities," Tournear said. “This means that we will incorporate any and all capabilities that fit our needs provided by whomever. This means we’ll team with [the Missile Defense Agency] to help with missile tracking, as an example, the Army and others for target custody, as another example, and commercial obviously wherever they can help.”

Moving fast

The SDA is unique among Department of Defense space organizations in its leaders are talking relentlessly about speed. The agency wants to get satellites operating in space almost immediately and aims for two year periods for upgrades. The agency’s leaders are taking a “better is the enemy of good-enough” approach, meaning that they’re interested in fielding technology as soon as feasible, not waiting until they have the best possible version before fielding it.

“We want capabilities to the war fighter by fiscal year 2022,” said Tournear. “Obviously going fast, we will risk having some failures. That’s OK.”

Griffin added that with threats changing every five years in space, it no longer makes sense to develop space systems over 10 to 15 years. By circumventing the traditional Defense Department acquisitions process, the SDA hopes to get their systems into space far faster and then be able to upgrade them regularly through software updates or by launching new small satellites.

Open to new ideas

Throughout the event, presenters emphasized that the agency was not committed to the notional architecture as laid out.

“We’re not wed to any of the concepts you see,” said Tournear.

Tournear and others encouraged industry representatives to respond to the agency’s recent request for information, which seeks input on the agency’s notional architecture. Responses are formally due Aug. 5, though Tournear said that the agency was open to suggestions at any time.

Nathan Strout covers space, unmanned and intelligence systems for C4ISRNET.