WASHINGTON — Gen. Mark Milley confronted a daunting challenge when he became chief of staff of the Army in 2015.

Virtually all of the Army’s recent modernization efforts — from the sprawling Future Combat Systems program, centered around a network that connected new vehicles, drones and other technology, to the Comanche helicopter to the Crusader weapon system intended to replace aging artillery — had ended in cancellation.

When Milley, who now leads the Joint Chiefs of Staff as the Pentagon’s top officer, became Army chief, he sketched out a new approach. Over his first several months in the position, he proposed a four-star command, dubbed “Army Futures Command,†that would ultimately lead the service’s modernization programs, grouped into six priority categories.

Milley saw the command as a new way forward, breaking free of the bureaucracy and silos that had hampered previous efforts.

“Here we are 40 years later, and the vehicles and weapon systems that were brought online when I was a lieutenant were still the vehicles and weapon systems — and organization and the doctrine are pretty much the same,†he told Defense News in an exclusive interview.

Over his four-year term as the Army’s chief of staff, Milley, working with top service officials, shifted billions of dollars into modernization programs and based the new command in Austin, Texas, an area known for its innovative, technology-focused workforce. The Army gave the command’s chief and the leaders of new groups, dubbed “cross-functional teams,†the authority to manage requirements and the leeway to direct dollars.

Now, four years into the experiment, top service officials are rethinking Army Futures Command, shifting it from an organization with control over investment decisions to an advisory body focused more on emerging technology and less on near-term programs. The move, they say, is meant to reaffirm civilian control of the military.

But the shift has raised questions about the future influence of the command and where the changes would leave the Army’s critical modernization efforts. It has also revealed a rare public schism among Pentagon leaders on how the service should approach modernization.

The divide comes at a critical time. The service hopes to get 24 new systems to soldiers by September 2023, an important milestone to prove the Army can move past its previous acquisition failures and address threats posed by Russia and China.

“We must transform quickly so we have continued overmatch against those who wish us harm and those who threaten our national security,†Army Chief of Staff Gen. James McConville said at the Association of the U.S. Army’s annual convention last fall.

“Our competitors have been aggressively investing in modernizing their forces with new technology and new weapons in order to maintain overmatch,†he added. “We must modernize now.â€

The beginnings of Army Futures Command

As Milley planned Army Futures Command, he wanted an organization entirely concentrated on fielding new equipment. Unlike Training and Doctrine Command, where modernization had to compete for attention alongside training, recruitment and professional military education, a more focused organization would enable the Army to move faster.

Even so, he said he faced skeptics in the Obama administration. Milley told Defense News that when he shared his ideas with Pentagon officials, he initially “did not get a lot of support.â€

But in early 2017, the Trump administration arrived, and Milley found a potential backer in acting Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy.

During an initial meeting at the Pentagon, McCarthy asked Milley to name his modernization priorities. Milley grabbed a paper dinner napkin on the desk and made a list.

Core to the Army and the first priority, Milley said, was fires. The military uses fires, such as artillery, to destroy or disable enemy forces’ ability to attack.

Next, he thought about movement, leading to the second and third priorities: a new combat vehicle and a vertical lift aircraft program.

To shoot and move in a coordinated manner, the Army would need to securely and reliably communicate, making the network the fourth priority.

“Then you have to be able to protect all of that,†Milley said, meaning the Army needs air defense, a capability considerably weakened when the Army shifted its focus to a counterinsurgency fight in the Middle East. Air and missile defense became the fifth priority.

“The last key function is to sustain†the force, he added, which leads to a focus on systems that enhance individual soldier capability — the final priority.

McCarthy was sold, and the two began hashing out the details. With the help of Army Secretary Mark Esper, who was confirmed in 2017, and Army Vice Chief of Staff Gen. James McConville, the four worked to make Army Futures Command a reality.

Milley and other top Army officials wanted the command to benefit from rapid technology development taking place at companies like Google and Amazon. Locating the headquarters in the tech town of Austin was meant to help the service learn how innovative businesses operate.

To lead the command, the Army tapped Gen. Mike Murray, who, as the Army’s G-8 chief, was in charge of making the service’s funding match up with its equipment needs. Suddenly, Murray went from wearing Army camouflage every day to donning button-down shirts and cowboy boots.

Milley said that was by design; civilian clothes made more sense in Austin because the uniform can be a “barrier.â€

But what the command really needed was money. Top service officials launched a process to cut other programs to find dollars for their new top priorities.

Through this approach, dubbed “night court†and led by McCarthy and McConville, the Army shifted, in the first round, more than $30 billion over five years away from projects that weren’t top priorities — like an Army lab effort to develop a bullet that would drop grass seed when it was shot — to the six priority areas.

In its first year, night court eliminated 41 programs and reduced or delayed 39 more. The Army, for example, canceled the Advanced Precision Kill Weapon System and a service life extension program for the Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System, and the service delayed the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle.

Esper also gave significant autonomy to the service’s four-star commanders overseeing forces, training, doctrine, materiel and modernization in the investment process. The idea was to allow leaders to quickly make decisions — whether for readiness or requirements.

Army Futures Command seemed to be taking root — but Milley said “a lot of antibodies†remained within the service.

Perhaps no group was more affected than the Army’s acquisition branch, which now had to contend with an entirely new command’s processes. The branch raised concerns AFC had too much freedom to direct funding and that its processes could undermine civilian control of the budget.

The tension between the acquisition office and the new command became most clear in the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle program, a competition to replace the Bradley fighting vehicle, a critical armored troop carrier.

In fall 2019, only General Dynamics Land Systems submitted a bid for the next phase of the program, despite the service’s efforts to create a competitive project.

Officials at Army Futures Command and those in the service’s acquisition branch clashed over whether the program could move forward, but the service ultimately started over, delaying the program by roughly two years.

Hoping to defuse the tension, McCarthy in 2020 issued a directive meant to clarify the authorities of AFC and those of the service’s acquisition office.

The order put Army Futures Command in the driver’s seat, establishing it as “leading the modernization enterprise.†It designated the command as the “Chief Futures Modernization Investment Officer acting on behalf of the Army†but noted it should work “in coordination with [the Army acquisition office], on all matters pertaining to research and development.â€

Army Futures Command was also starting to win supporters in Congress.

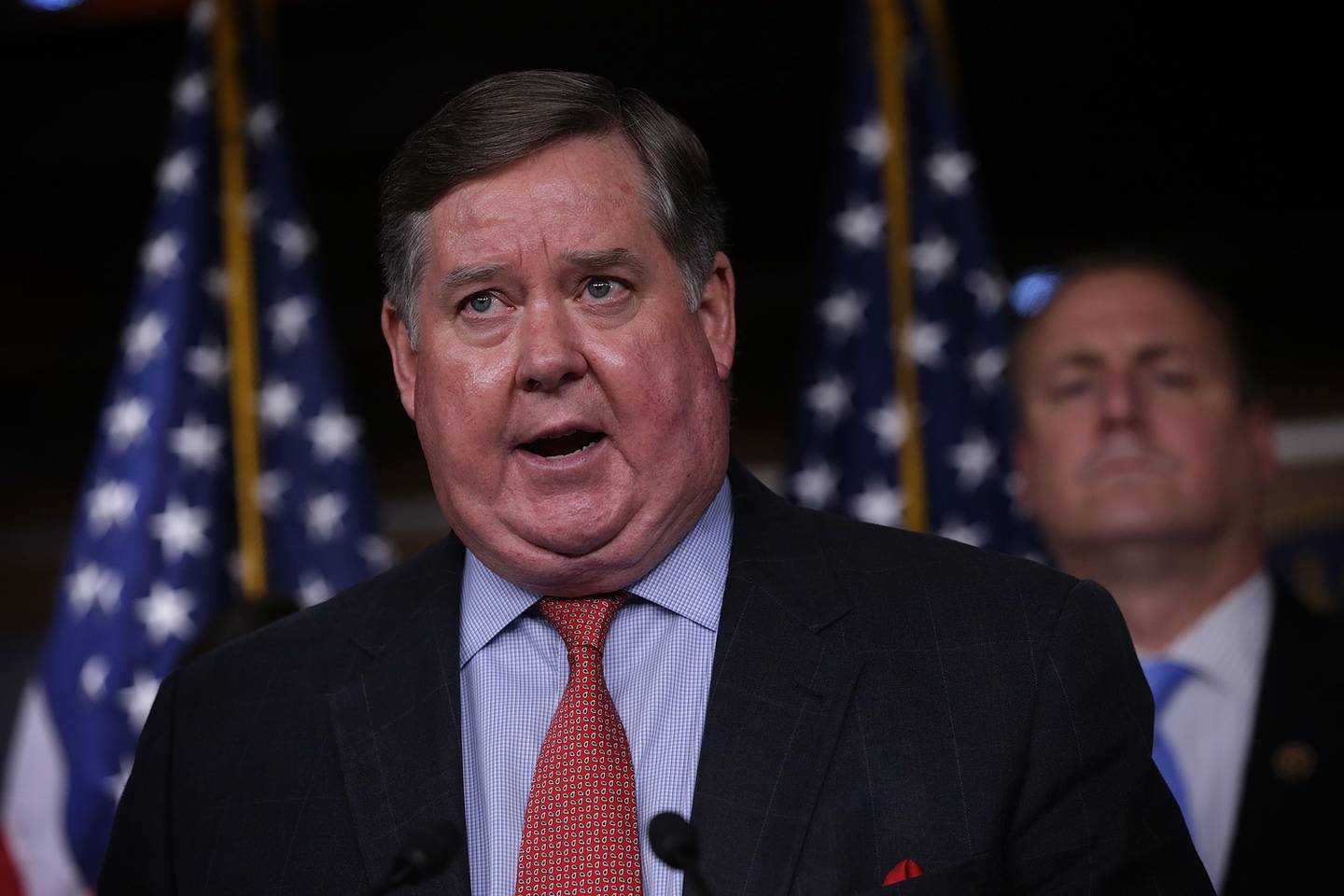

“I had my doubts in the beginning,†Rep. Ken Calvert, R-Calif., the ranking member of the House Defense Appropriations Subcommittee, told Defense News in a recent interview. He said he questioned whether it cost too much and was in the right location — even “the entire concept.â€

But, he added, “I was always in favor of doing things differently than what has been done in the old Army because, obviously, that wasn’t working.â€

A new administration

Army Futures Command received attention and gained traction as it opened its headquarters in downtown Austin in August 2018. Across the street, it opened the Army Applications Laboratory, which helped startups meet the service. The lab was based at the Capital Factory, a hub connecting entrepreneurs with investors.

Milley said the command was able to bring “more successful programs in the last 24 months to actual reality, at least an initial operating concept, than the Army did in the previous four years.â€

Although some of those efforts were already in development, the command has touted it was able to push programs through development and into soldiers’ hands faster than previously planned.

In 2021, the Army delivered a new short-range air defense system to Europe; the service now is working to field the same system with a 50-kilowatt laser capability in fiscal 2022.

Also last year, the service bought and fielded two Iron Dome systems for Indirect Fires Protection Capability, briefly deploying one to Guam. In addition, the Army delivered Enhanced Night Vision Goggles.

This year, soldiers are on track to get a new air and missile defense sensor, a command-and-control capability, the mixed-reality Integrated Visual Augmentation System, and the Next-Generation Squad Weapon.

After Christine Wormuth became Army secretary in May 2021, she made two visits to Army Futures Command’s headquarters. She told Defense News she quickly identified some “ambiguity†in the direction given to the command and the service’s acquisition office about their roles and responsibilities.

At the same time, Wormuth moved to centralize investment authority in Army headquarters.

Then, in May 2022, she issued a memo voiding previous Army modernization directives and shifting much of AFC’s control over funding back to the acquisition branch. This included funding for laboratory research as well as development and prototyping.

Wormuth told Defense News the memo was meant to “make some minor adjustments to the relationship between†the acquisition office and the command.

“I didn’t want to make any changes through that directive that would get in the way of delivering results,†she added.

But Calvert said the new directive “basically guts the entire intention of the Army Futures Command.â€

“Why the hell did we do it in the first place?†he said. “If bureaucrats want to take over the operation and tell the military to take a back seat … that’s just an entire bureaucratic power play from my perspective, and we’re going to be back to where we were.â€

Thomas Spoehr, a former three-star Army general once in charge of force development who now works at the Heritage Foundation think tank, said Wormuth’s directive has left the “perception — whether correct or not — that the Army headquarters is seeking to rein in AFC.â€

“That impacts their ability to get things done,†he said of Army Futures Command.

Army officials have pushed back on claims they weakened the command.

“Army Futures Command never had acquisition authority,†Doug Bush, the Army’s acquisition chief, stressed in testimony on Capitol Hill this spring. “That has always resided, as required by law, on the civilian secretariat side in my office.â€

The AFC commander’s “got his job, I’ve got mine. No one person is in charge of everything,†he added.

The Army has not named a new AFC chief since Murray left in late 2021. According to multiple sources who weren’t authorized to discuss the matter publicly, Lt. Gen. Walter Piatt was the front-runner for the job. However, he reportedly was reluctant to send the National Guard to stop the Jan. 6 insurrection, spurring concerns his nomination wouldn’t survive a Senate confirmation process.

With no one in the top job, Lt. Gen. James Richardson, Murray’s deputy, is serving as acting commander. He has made few public appearances, and the command has returned to wearing military uniforms more regularly at the request of the new command sergeant major.

Spoehr said leaving the command without a chief is “inexplicable.â€

“I am not aware of an Army four-star command ever going this long without a nomination for a commander,†he added. “There is no substitute for a confirmed four-star commander when the command deals with the Pentagon officials, industry and the public. People know four-star generals are a rare breed.â€

Wormuth said the Army is working to name a new commander, and she remains “very hopeful that we will see a nominee going to the Senate in short order.â€

The path forward

The Army’s modernization programs have a busy year ahead. By the end of this fiscal year, the service is slated to choose a team to build a new long-range assault aircraft.

The Army is also on schedule to deliver in FY23 a new long-range Precision Strike Missile; a cannon capable of shooting out to 70 kilometers; a long-range hypersonic weapon; a ship-killing midrange missile; a new lightweight tank; the Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle; and a new tactical unmanned aircraft system.

In a recent interview, Wormuth and Bush vowed Army Futures Command will remain in Austin and have a four-star chief. And, along with McConville and Richardson, they confirmed their commitment to seeing the service’s modernization priorities to the finish line.

But Wormuth told Defense News she sees the command evolving to focus on thinking about the longer-term future rather than on programs for the next decade.

According to her directive, the command “is responsible for force design and force development and is the capabilities developer and operational architect for the future Army.â€

“AFC assesses and integrates the future operational environment, emerging threats, and technologies to provide warfighters with the concepts and future force designs needed to dominate a future battlefield,†it added.

The command should be “helping us think about where we need to be not just in 2030, but thinking ahead to the Army of 2040,†Wormuth said, adding that the organization “is fundamentally about doing a lot of conceptual work.â€

Now, Wormuth is focused on pushing a total of 35 signature systems into soldiers’ hands by 2030. About 24 will either enter the field or be in late prototyping phases by the end of FY23.

But Congress wants more answers about who is overseeing the Army’s modernization work. A provision in the House version of the latest defense authorization bill, submitted as an amendment by Rep. Mikie Sherrill, D-N.J., requires the service to prepare a plan that “comprehensively defines the roles and responsibilities of officials and organizations of the Army with respect to the force modernization efforts of the Army.â€

If the Army fails to submit this plan on time, the head of Army Futures Command will revert to the roles and responsibilities laid out during the Trump administration. In other words, Wormuth’s latest directive would “have no force or effect.â€

How Army modernization goes in the coming years could also influence Milley’s effort to create a joint futures command that would encompass all of the military services.

He considers Army Futures Command “an enormous success.†This model, he told Defense News, could pave the way for the joint force to determine what it will need to operate successfully in the future.

“As we go forward, we need to make sure [the Army] maintains that momentum that it’s built,†Milley said, “which is actually leading the way for joint modernization.â€

Jen Judson is an award-winning journalist covering land warfare for Defense News. She has also worked for Politico and Inside Defense. She holds a Master of Science degree in journalism from Boston University and a Bachelor of Arts degree from Kenyon College.