ARLINGTON, Va. — Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks last week rolled out Replicator, a new Pentagon drone program to compete with China.

The announcement was heavy on goals: to field thousands of drones across multiple domains in the next two years to outcompete China’s industrial advantages. But left unanswered was how the program would be funded, what role industry would play and why the program was coming now.

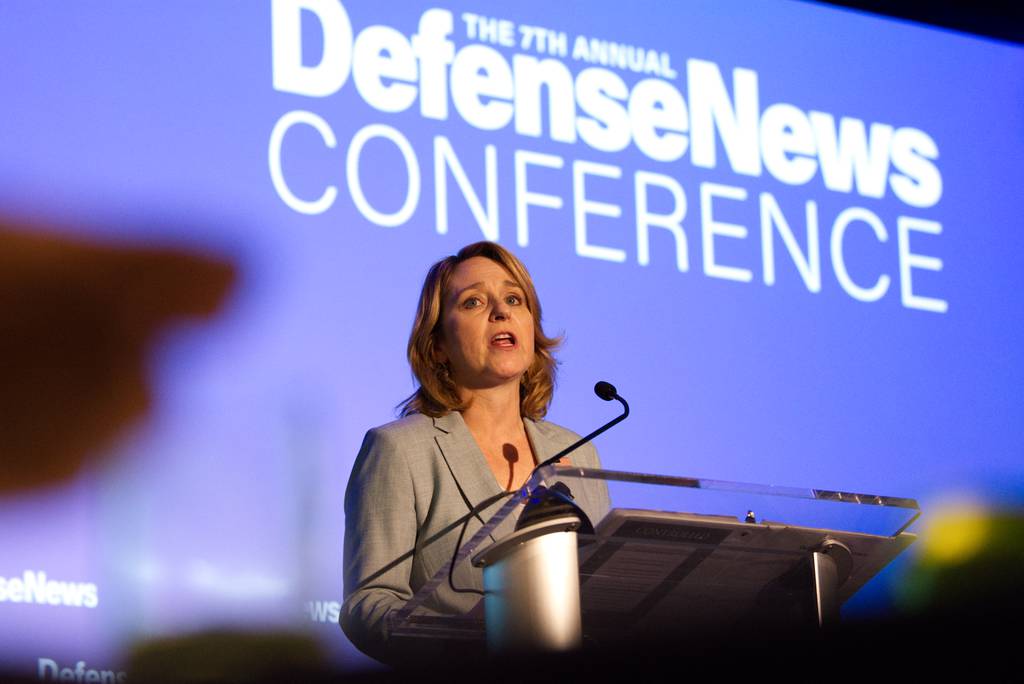

At the Defense News Conference on Wednesday, Hicks answered many of those questions.

First, Replicator will not need new money. Instead, she said the program will pool already funded programs from the military services. Defense Innovation Unit Director Doug Beck, she said, is already canvassing the services for programs to bring forward.

“We’re not creating new bureaucracy, and we will not be asking for new money in [fiscal 20]24,” Hicks said. “Not all problems need new money.”

She acknowledged this approach might generate skepticism. How can a Department of Defense initiative promise lasting innovation without establishing a program of record?

Hicks argued the attention of leadership will compensate. Replicator, she said, falls under the charge of the Deputy’s Innovation Steering Group, or DISG, chaired by Hicks and the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Their ability to trim red tape, she said, will accelerate the effort.

Second, Replicator is focused on competing with China. But its arrival doesn’t mean the Pentagon has new intelligence on China’s intentions.

“We’ve said before that conflict with the PRC is neither imminent nor inevitable,” Hicks said. “That remains our assessment.”

Replicator, according to Hicks, has two overarching goals. One is to strengthen the deterrence already preventing conflict on the Taiwan Strait. The other is, in the event of conflict, to make sure the U.S. has an edge.

“We never want to find ourselves in a situation where, in the words of [former Defense] Secretary Bob Gates, ‘The troops are at war, but the Pentagon is not,’” she said.

Still, what Replicator will look like in action remains vague. The most concrete example Hicks pointed to is from the private sector: groups of small, low-flying satellites — such as Starlink’s, which Ukraine relies on for intelligence and internet connection.

Whether the Pentagon’s vast bureaucracy can move so nimbly remains to be seen. Hicks said “there are concerns” about whether industry can meet the ambitious two-year timeline, especially without a new program of record.

“We are worried about proving out with all parties that the department can actually lead itself [and] does not get mired in red tape,” said Hicks.

Noah Robertson is the Pentagon reporter at Defense News. He previously covered national security for the Christian Science Monitor. He holds a bachelor’s degree in English and government from the College of William & Mary in his hometown of Williamsburg, Virginia.